In a recent paper with Scott Page, forthcoming in Management Science, we show that when combining the forecasts of large numbers of individuals, it is more important to select forecasters that are different from one another than those that are individually accurate. In fact, as the group size goes to infinity, only diversity (covariance) matters. The idea is that in large groups, even if the individuals are not that accurate, if they are diverse then their errors will cancel each other out. In small groups, this law of large numbers logic doesn’t hold, so it is more important that the forecasters are individually accurate. We think this result is increasingly relevant as organizations turn to prediction markets and crowdsourced forecasts to inform their decisions.

Many people, including myself, have been a little disturbed by the wild celebrations of Osama bin Laden’s death. An article in the New York Times quotes a number of psychologists that explain the partying as natural cathartic “pure existential release.” It’s not until the last two paragraphs of the article that they hit on what I think was the real driving force behind the “chanting and frat-party revelry”: crowd dynamics. The article says, “in a crowd of like-minded people, the most intense drives for justice become the norm: People who may have felt a mix of emotions in response to the news can be swept up in the general revelry.”

The dynamic is similar to that detailed by Cass Sunstein in his book Going to Extremes (I’m currently writing a paper that develops formal models to explain the going to extremes dynamic). Sunstein describes a pile of social psychology research demonstrating that when like minded individuals discuss their opinions, they become more extreme, rather than converging to the mean. A prime example is risk taking among teenagers, a bunch of kids that would never try driving their car 150 miles an hour or shotgunning cases of beer on their own, will turn into drunken race car drivers in a crowd of their peers. I imagine the dynamic was much the same around the Georgetown bars last Sunday night. Riots can erupt the same way. Most people wouldn’t think of throwing bricks threw store windows or setting cop cars on fire, but in the midst of a rioting crowd our behavior can be much different.

This article in Wired covers new research on networks and information by Sinan Aral (Northwestern B.A. in Political Science, MIT Sloan PhD, now at NYU Stern) and Marshall Van Alstyne. The article describes research on the email communications of members of an executive recruiting firm, and says, “those who relied on a tight cluster of homophilic contacts received more novel information per unit of time.” The article is confusing though because it mixes several distinct network concepts: homophily, strong ties, clustering, and “band width.” Homophily is the tendency for people to be connected to other people that are similar to them; birds of a feather flock together. In his seminal paper, “The Strength of Weak Ties,” Mark Granovetter defined the strength of a tie as “a (probably linear) combination of the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding), and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie”. Clustering measures the tendency of our friends to be friends with each other. And bandwidth is a less standard term in the social networks literature that captures the total amount of information that flows through a given tie per unit time (and thus is about the same thing as strength of a tie).

After reading the Wired piece, I’m left wondering if it is

- strong or “high bandwidth” ties through which we communicate a lot of total information,

- homophilic ties with people that are similar to us,

- ties with people that are members of a tightly knit cluster of friends, or

- all of the above

that provide us with the most novelty in our information diet.

A look at the original research article makes it more clear why the Wired article was so confusing. The actual argument has a lot of moving pieces to it. The first argument is that structurally diverse networks tend to have lower bandwidth ties. Here structurally diverse appears to mean not highly clustered. So, you talk more to the people in your personal clique than to people outside of your tightly knit group. The second piece relates structural diversity to information diversity. They find that the more structurally diverse the network, the more diverse the information that flows through it. So far, this seems to line up with the standard Granovetter weak ties story. The third relationship is that increasing bandwidth also increases information diversity, and more importantly, increasing bandwidth increases the total volume of new (non-redundant) information that an individual receives. The idea here is that if you get tons of information from someone, some of it is going to be new.

Finally, since both structural diversity and bandwidth increase information diversity, but structural diversity decreases with increased bandwidth, they set up a head to head battle to see whether the information diversity benefits of increasing bandwidth outweigh the costs of reducing structural diversity. They have three main findings on this front that characterize when bandwidth is beneficial:

- “All else equal, we expect that the greater the information overlap among alters, the less valuable structural diversity will be in providing access to novel information.”

- “All else equal, the broader the topic space, the more valuable channel bandwidth will be in providing access to novel information.”

- “All else equal, ... the higher the refresh rate, the more valuable channel bandwidth will be in providing access to novel information.”

The burst of Twitter reports of Bin Laden’s death prior to any official announcements is continuing to generate interest. NPR has an informative interview with Andy Carvin, NPR’s senior strategist for social media (thanks to Georgia Kernell for sending it to me). The event raises several interesting questions about social dynamics and the spread of information. It would be interesting to know how many false reports of Osama Bin Laden’s death there have been on Twitter prior to this that didn’t “go viral.” It would seem that a key feature of this particular cascade of tweets was the apparent authority of the “earlier adopters.” The initial tweet that got things going seems to have come from a former aide to Donald Rumsfeld. This tweet was probably picked up by other “Beltway insiders.” I would guess a key feature to the rumor’s success in spreading was the fact that these initial tweeters were people that other people trusted to know this sort of thing. That’s a difficult aspect to capture in basic compartmental models of rumor spreading, or even standard network models of information transmission. You not only need to have highly credible individuals, but you have to have a large cluster of credible individuals that are all tightly connected to one another.

By now many people have heard of how Twitter predicts the stock market. The Media Decoder blog at the New York Times has an entry today on how Twitter contributed to the leak of Osama Bin Laden’s death. A follow-up article was posted later.

Highlights:

“Unconfirmed reports — that turned out to be true — of Osama bin Laden’s demise circulated widely on social media for about 20 minutes before the anchors of the major broadcast and cable networks reported news of the raid at 10:45 p.m., about an hour before Mr. Obama’s address from the White House.”

“Twitter saw the highest sustained rate of posts ever, with an average of 3,440 per second from 10:45 p.m. to 12:30 a.m. Eastern time. There were more than five million mentions of Bin Laden on Facebook in the United States alone.”

The New York Times makes another tipping point claim today. This one seems more believable: “For many gay rights advocates, the decision amounts to a turning point in the debate — the moment at which opposition to same-sex marriage came to look like bigotry, similar to racial discrimination and the subordination of women.” Attitudes regarding gay marriage (and segregation, women’s rights, ...) are social norms, and norm formation is a process that social scientists have studied and modeled extensively. Almost all of these models do exhibit tipping behavior. Whether or not this is in fact the tipping point for norms regarding the definition of marriage is an empirical question, but such a tipping point almost certainly exists.

In today’s New York Times, Robert Shiller argues that the recent crisis should precipitate a movement to collect better data that could help in predicting similar events in the future. He likens the problem to predicting hurricanes; something that was impossible at one time, but which we can now do accurately because of better data. Shiller’s point is a sharp contrast to the perspective of Duncan Watts espoused in his recent book, Everything is Obvious (Once You know the Answer). Watts argues that no matter how good the data, predicting many things is just impossible, in part because its impossible to even know what it is you should be predicting. Shiller’s opinion on this matter has an extra sense of authority of course, because he is one of the few economists who saw the housing bubble/credit crunch/financial crisis coming and said something about it. He also forecasted the stock market collapse of 2001.

So, who’s right? Is Shiller just another example of luck and large numbers? After all, a lot of people are making a lot of predictions out there, so we shouldn’t be surprised that someone got it right. And Watts’ argument that in many cases we can’t know what we should have been predicting until we put the outcome in a context has merit. Both are right to an extent. I do believe the crisis was predictable, and that Shiller wasn’t just lucky in foreseeing it, but I also agree with Watts that more data isn’t the full solution. We also need to know where to look — how to put that data together. We can forecast hurricanes today not just because we have better data, but because we have better models and a better understanding of how the weather works. It’s a little surprising that Shiller doesn’t point this out, because he is also well-known for arguing that economists should in part be looking in a different direction than they have in the past. Namely, our economic models need to incorporate more social and psychological effects (see his recent book with George Akerlof, Animal Spirits).

This article in the New York Times describing a “tipping point” in the effect of gas prices on the economy is a good example of bad use of the term tipping point. Unfortunately, the term has become so popularized that it has lost a lot of its meaning (Scott Page and I try to resurrect it in a recent paper that’s currently under review). The gist of the article is a simple model that goes like this:

- When the economy gets better, gas prices rise.

- When gas prices rise, growth slows down.

- Economic growth is a self-reinforcing process — the bigger the economy, the faster it grows.

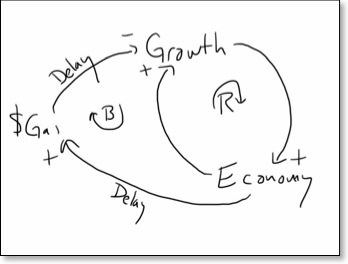

From a system dynamics perspective there are two feedback loops in this model: the reinforcing loop of economic growth and the balancing loop that goes through gas prices. Since the links between the economy and gas prices and gas prices and growth both have delays in them, this structure leads to oscillation in both gas prices and the economy. The economy grows, leading to more growth. Eventually gas prices catch up and start to slow economic growth until it begins to decline. At this point, growth is negative leading the economy to shrink, leading to more negative growth as the reinforcing feedback works in the opposite direction. Eventually gas prices fall low enough to start the recovery, and the oscillation repeats. The article suggests that we may be reaching the top of one of the peaks in the economy, at which the rise in gas prices causes growth to go from positive to negative. But this is not a tipping point. At a tipping point, a small change causes a big change. In this case, if we believe this model and that we’re at the crest of one of these cycles, a small increase in gas prices causes a small decrease in the growth rate. It just happens to go from very slightly positive to very slightly negative, but this is still a small change — not a tip.

As anyone with a fantasy football team can tell you, predicting the success of NFL players in their rookie year is a tough business. Now NFL teams may have a new tool: content analysis. A company called Achievement Metrics is analyzing the content of college player’s post game press interviews to predict characteristics like leadership, discipline, and behavior risk. They use the same techniques to predict how likely an individual is to be a terrorist. There’s an article on their approach here.

My friend, collaborator, and mentor Scott E. Page was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences this year. Congratulations Scott! Scott is best known for his work (with Lu Hong) on the benefits of diversity for problem solving. Together, Scott and I have written papers on group forecasting, tipping points, and markets with positive feedbacks. Scott’s Ph.D. is from the MEDS Department at Kellogg.